Research shows how Late Romans used educated guesswork to interpret ancient hieroglyphic writing

It may be some comfort to any Latin student who has ever had to improvise their way through a difficult translation to know that even well-educated Romans were not above doing the same sort of thing.

That, at least, is how one ancient historian seems to have dealt with the challenge of deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphics, according to new research which shows how – rather like many people today – Romans sometimes interpreted the relics of their ancient antecedents by using educated guesswork to supplement what they actually knew.

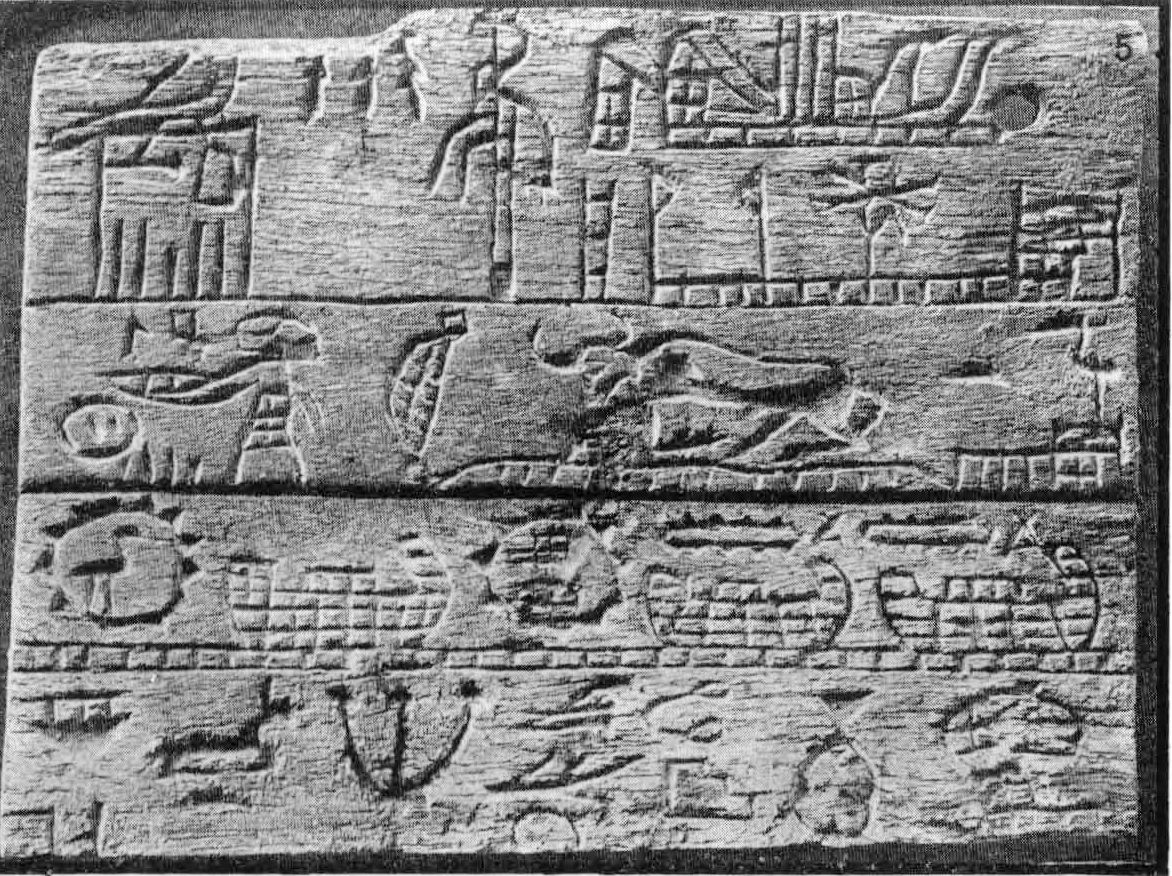

The newly-published study, by Dr Frances Foster at the University of Cambridge, also explains a mysterious passage in the work of Ammianus Marcellinus, the fourth-century CE historian in question. In his Res Gestae (a history of imperial Rome), Ammianus used two bizarre examples to describe how hieroglyphs functioned as a writing system. One attempted to explain the use of bees to symbolise kingship, while the other appears to suggest that vultures symbolised ‘nature’ because – so he alleged – vultures were exclusively female.

Some historians have since argued that Ammianus had been suckered by ‘fairy-tales’ about hieroglyphs’ supposedly mystical meanings, but Foster suggests that his interpretation deserves a second look. She argues that like most Romans then, and many audiences now, he was actually drawing on what he knew about hieroglyphs, and improvising around that understanding to fill in the gaps.

"For Ammianus, Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs had already been dead for centuries. It was like Latin is to us, only even more obscure."

Foster teaches ancient education at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge, and studies how people read, understand and process ideas from the ancient world. “We can learn a lot by looking at how older societies read their own ancient past,” she said. “Ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs in the time of Ammianus are a case in point. For him, that language had already been dead for centuries. It was like Latin is to us, only even more obscure.”

Ammianus’ strange discussion of hieroglyphs appears in a passage in which he describes obelisks in the Egyptian city of Thebes. “Individual characters served as individual nouns and verbs, and sometimes they signified whole ideas,” he told his readers. This was not strictly true: hieroglyphs were largely phonetic, but by Ammianus’ time, some Egyptian priests had deliberately promoted the idea that they also had cryptic, pseudo-magical meanings.

Ammianus then writes that a king was symbolised by a bee making honey, because “in a ruler, stings also ought to arise from sweetness”. He then claims that a vulture was the symbol for the Latin word natura (often translated as ‘nature’) “because no males can be found among these birds”.

Perhaps surprisingly, Foster’s research suggests that these odd attempts at translation were not entirely misguided. “He couldn’t read the hieroglyphs, but when you look, there is evidence that he knew something about the meanings, and could get half-way there,” she said.

A bee making honey, for example, really is often translated by scholars as ‘Dual King’, because it refers both to the role of a king and to royal ancestry. Foster thinks that Ammianus knew that the symbol had some sort of double meaning, but unaware of what that was, guessed that Egyptians saw their ideal ruler as one who balanced sweetness with harshness. The translation was almost right; the explanation ingenious – but completely wrong.

"Like us, Ammianus relied on the best educated guess he could make to complete the picture."

His odd interpretation of the vulture is more obscure: but Foster points out that many ancient scholars – including Aristotle, for example – claimed that vultures were exclusively female, and procreated with the wind.

This offers an important clue about Ammianus’ use of natura when translating the vulture, as the Latin word can also mean ‘organs of generation’. Once this is understood, it turns out his translation was not far off: the vulture really did feature in ancient Egyptian words meaning ‘mother’, ‘uterus’ and ‘womb’. Again, his attempt to explain the translation is what makes it seem outlandish today.

“This is an example of how Romans looked at the ancient world very much in the same way we might interpret ancient exhibits in museums now,” Foster said. “Often, we only know a little bit about what we are looking at, and like us, Ammianus relied on the best educated guess he could make to complete the picture.”

Foster also points out that his elaborate explanations were more than an attempt at translation. Rather like people who may have studied Latin to GCSE today, he was, she thinks, using the fact that he had a better grasp of an old, elite language to ‘show off’ to his less-initiated readers.

The research also provides a glimpse of how our command of languages and their cultural meaning changes, as the cultures to which they belong themselves disappear. Ammianus’ generation was one of the last in which anyone alive could read Egyptian hieroglyphs properly. “The phonetic use of Egyptian hieroglyphs was being distorted by the idea that it was something pictographic and mystical – a misconception that many people still have,” Foster said. “Ammianus had a foot in both worlds, and we can see that from his mixed interpretation of the meanings behind the symbols he saw.”

The article is published in The Classical Quarterly and is available open access.