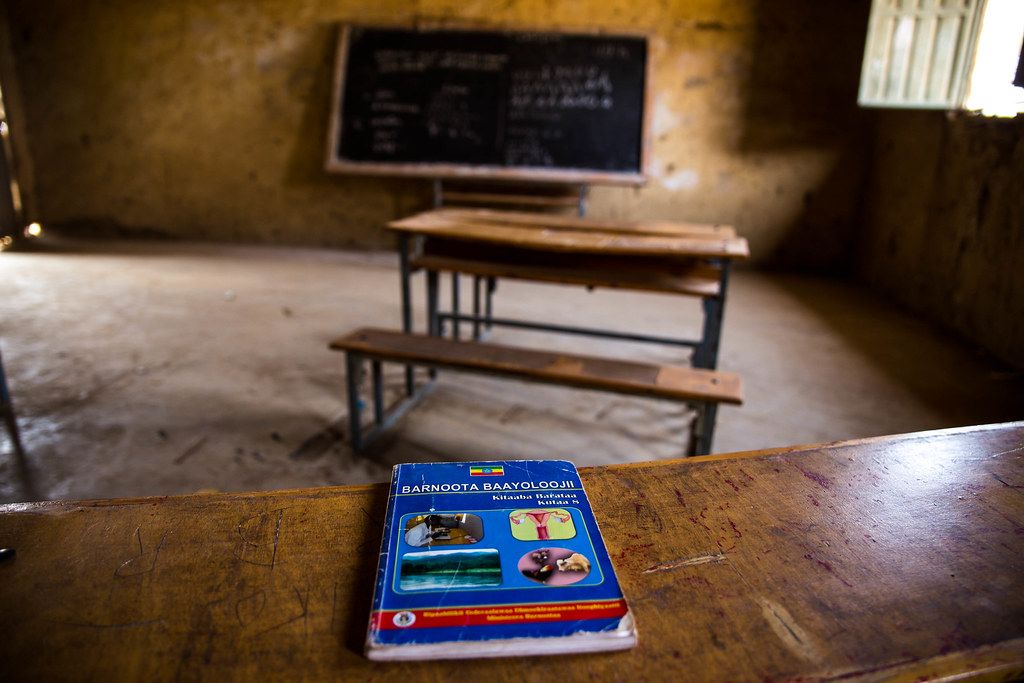

In Ethiopia, schools still lack basic means to contain COVID-19, as pupils return after months of interrupted learning

Many schools in Ethiopia lack the hygiene facilities and infrastructure to control COVID-19 effectively, as they reopen for the first time after months of disrupted learning, new research indicates.

The two new research and policy reports, compiled by academics at the University of Cambridge in collaboration with partners in Ethiopia, draw attention to the combined educational and practical challenges facing the country’s schools as pupils return. The authors suggest that these converging problems, while more severe than those affecting schools in wealthy countries such as the UK, are typical of those confronting millions of parents and teachers across sub-Saharan Africa as the pandemic continues to exact a far less-visible toll on their lives and communities.

The findings are based on telephone interviews with more than 900 teachers and caregivers which were carried out in August. Schools in Ethiopia are currently reopening on a staggered basis for the first time since March, with priority given to schools in rural areas. Since the study was completed, many of the issues it documents will have been compounded by the crisis in Tigray.

Overall, the researchers found that, despite significant efforts by the Ethiopian government to support remote learning, many pupils are likely to have had little or no education during the closure period. Disadvantaged groups – such as poorer children, those in remote areas, and girls – are likely to need specific attention having missed out the most.

But while it is therefore vital that schools reopen, the reports also highlight the huge challenges of making schools COVID-safe at a time when access to a vaccine is still, in all likelihood, months away for many teachers and pupils. They point to cases where schools lack soap and running water, for example, and to concerns about the practicalities of social-distancing in overcrowded classrooms.

In many parts of the world, COVID-19 has not just made it harder to keep children learning: it also makes it harder to keep them in school.

The surveys were undertaken by members of the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge, in partnership with colleagues at Addis Ababa University and the Ethiopian Policy Studies Institute, as part of the RISE Ethiopia and Early Learning Partnership projects.

School closures are widely understood to have deepened a long-term ‘learning crisis’ in low- and middle-income countries in which many of the least-advantaged children already struggle to attain basic levels of literacy and numeracy. Professor Pauline Rose, Director of the REAL Centre, said: “These reports describe the situation in Ethiopia, but highlight interlocking problems that apply much more widely.”

“In many parts of the world, COVID-19 has not just made it harder to keep children learning: it also makes it harder to keep them in school. There are multiple constraints affecting low- and middle-income countries which mean that the very poorest and most marginalised children are even greater risk of dropping out of the system altogether than they already were.”

With schools reopening it is essential that policy-makers have access to the sort of evidence presented here. It is critical to targeting those pupils who need the most support, and limiting the effects of lost learning for millions of children.

Professor Tassew Woldehanna, President at Addis Ababa University, said: “With schools reopening it is essential that policy-makers have access to the sort of clear, robust evidence presented here. It is critical to targeting those pupils who need the most support, and limiting the effects of lost learning for millions of children.”

The team interviewed 443 primary school teachers and principals and 480 parents and caregivers. They also co-ordinated with surveys by the Oxford-based Young Lives programme, who spoke to a further 64 principals.

Their results show that while many teachers have been quick to adapt to remote teaching and learning, students’ access to education has clearly been uneven. In some rural regions, for example, none of the teachers interviewed had internet access and only around half of households had electricity. The researchers estimate that around two-thirds of the teachers they surveyed had reached fewer than half of their students during the closures.

The uneven provision that this implies is likely to have affected disadvantaged groups, such as poorer children, those in rural areas, and girls (whose education is often considered lower-priority than that of boys), most severely. Many teachers fear that, because these groups’ parents often have low literacy, low regard for education, and recruit their children to support the generation of family income; such children are especially at risk of dropping out of school, or of never returning.

The research also draws attention to COVID-19’s impact on pre-primary education in Ethiopia: a sector which has been neglected by many governments during the pandemic. Only 53% of parents or caregivers with young children had been able to engage in learning activities with pre-primary children during school closures. Just 10% reported any contact with pre-primary teachers.

At the same time, however, the reports highlight significant infrastructure and resource challenges within schools themselves. 38% of parents said that their children’s schools were only ‘somewhat equipped’ with handwashing facilities; 22% said that they were ‘not equipped at all’. About 15% said that they did not have facemasks for their children to wear at school, and 46% could not provide their children with hand sanitiser. A majority of teachers and principals, especially those in rural areas, expressed similar concerns about both hygiene, and a lack of adequate classroom space to maintain social distancing.

The researchers stress that despite the efforts made by the government so far, ongoing interventions will therefore be needed to help all children benefit as schools reopen. Their main recommendations are:

- A targeted, national campaign by government, school management committees and local authorities to keep children in school.

- Extra support (and, if viable, time in school) for students who need to recover lost learning.

- The construction of new classrooms or sheltered areas where possible, as well as the targeted supply of extra hygiene resources such as sanitisers, facemasks and handwashing facilities to those most in need.

- Additional investment in resources and strategies to support remote learning, particularly in the context of further possible outbreaks in schools before the effective delivery of a vaccine.

Both reports are available from the REAL Centre website.