Universities under attack?

Project to examine ‘constellation’ of political pressures reshaping Higher Education

Researchers have launched a three-year, international study which aims to examine political and economic pressures that are changing the fundamental role and character of universities globally, particularly in relation to their mission to serve a wider ‘public good’ and to reduce societal conflict.

The ‘Higher Education, States of Precarity and Conflict’ project will seek to illuminate the effects of what it describes as a ‘constellation of pressures’ which appear to be jeopardising Higher Education’s independence and, with it, its future public role – among them threats to liberal democracy, public sector cuts, and rising inequality.

The project team, led by researchers at the University of Cambridge, hopes to provide insights that will better equip academics and education professionals to defend their right to teach and research free from economic and political pressures that sometimes amount to interferences or hindrances. Doing so, they argue, would allow universities to reclaim their public mission: particularly in relation to civic engagement, academic freedom and the reduction of political conflict, including the exigencies of war and violence.

"Each of these four countries is undergoing some sort of crisis of the state. We want to understand more about how that translates into threats to universities’ autonomy and their public mission."

The research will focus on four nominally democratic states where Higher Education’s capacity to discharge that function appears to be under threat. One is the UK, where, among other pressures, budget cuts, Brexit and counter-terrorism initiatives have affected university policy in recent years undermining teaching and research, and where campuses are now becoming lightning rods for fabricated ‘culture war’ disputes. The others are South Africa, Hungary and Turkey, where universities in many cases face more urgent crises, including stringent security measures, human rights abuses, and Government suppression of teaching and research.

Professor Jo-Anne Dillabough, from the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge and the project lead, said: “Each of these four countries is undergoing some sort of crisis of the state. By looking at them together, we will be able to understand more about how that translates into threats to universities’ autonomy and their public mission.”

“Most universities were founded on liberal principles – such as academic freedom and freedom of speech – but in some ways this means that they are naturally contested spaces which absorb political tensions, dilemmas and conflicts. At present, this is not just intensifying but challenging that freedom directly, as they come face to face with modern political crises and state experiments.”

While the project identifies the most conspicuous examples of geopolitical change – notably rising far-right populism – among that list of pressures, it also highlights various other forces that threaten to transform Higher Education internationally.

These include, for example, changes to how research and tertiary education are funded, or demographic changes such as the influx of refugee students and academics into Turkey from Syria. The project will also examine the causes and effects of grass-roots challenges to universities to which their administrations have often been slow to respond; one early paper, for example, interrogates persistent failures to acknowledge or resolve cases of racial injustice on campuses.

In the UK, Higher Education has for some decades been the scene of what the team characterises as ‘cold’ conflict, with public and political debates playing out with peculiar intensity in universities compared with other public spaces. Examples include controversies over the implementation of the Government’s counter-terrorist ‘Prevent’ strategy, and more recently, well-publicised arguments about free-speech and the no-platforming of controversial speakers.

One of the first studies published through the project also suggests that the ‘marketisation’ of British Higher Education – notably in the form of rising student fees – has helped to fuel anti-establishment politics by creating a generation of disillusioned graduates who, having failed to reap the promised rewards of an increasingly expensive, high-stakes university degree, are unusually vulnerable to the ‘politics of resentment’.

Contrastingly, the other three countries that will be studied are cases where higher education has become a battleground for ‘hot’ conflict, often with more urgent consequences.

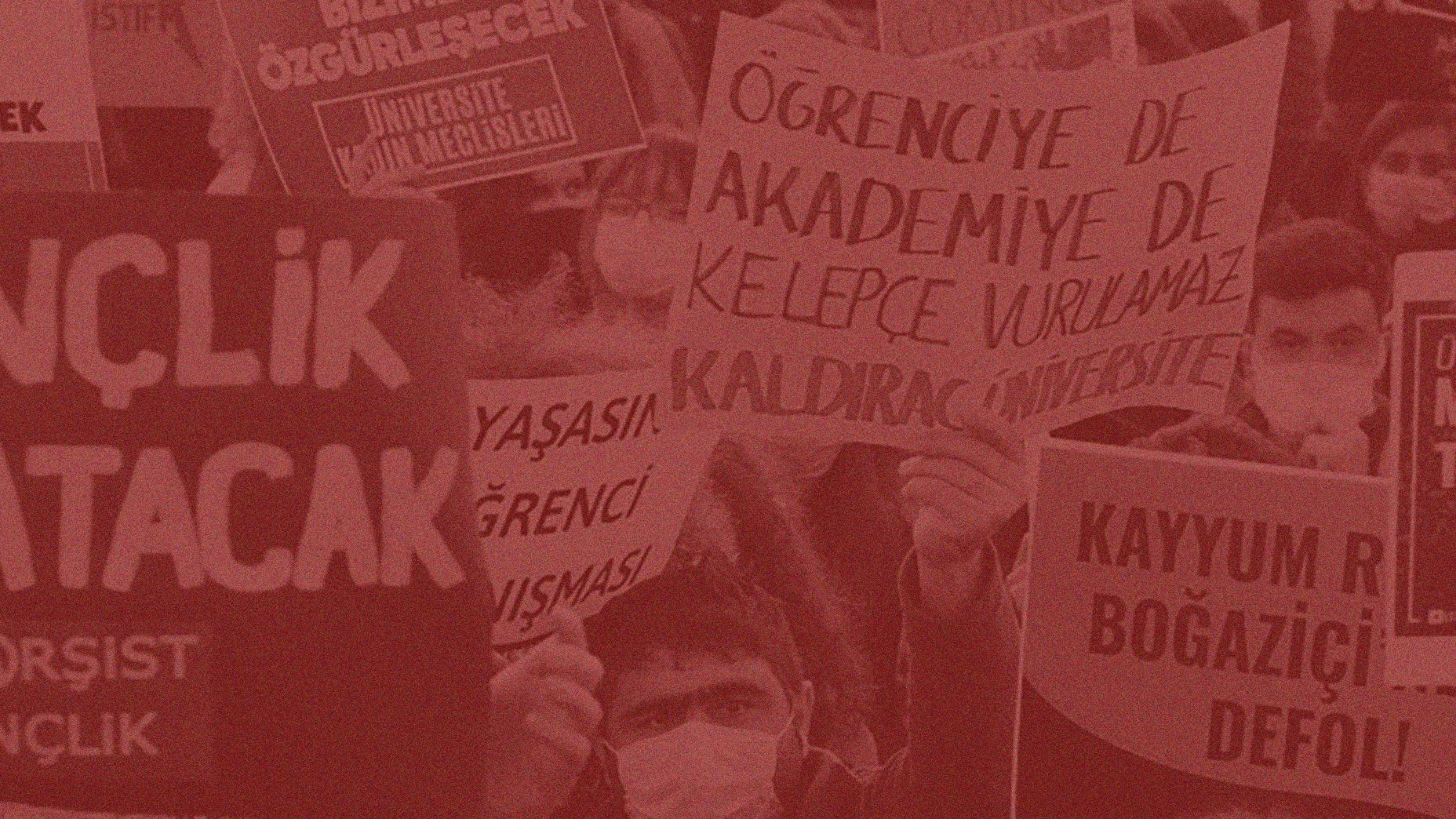

In Turkey, which is perhaps the most extreme case, Recep Erdoğan’s Justice and Development Party has dismissed tens of thousands of public service personnel – many of them academics or university staff – and imprisoned thousands of staff and students, while closing universities to silence opposition to the Government.

A corresponding war on universities has been perpetrated by the populist right in Hungary under Viktor Orbán, where subjects such as gender and migration studies have been removed from curricula because of their incompatibility with the state’s ambitions to become an illiberal, nationalist and Christian ‘illiberal democracy’. And in South Africa, notoriously high murder and crime rates have led to restrictive student surveillance policies, while universities are also being challenged by numerous new populist movements – such as the Fallists, Black First Land First, the EFF, and far-right Afrikaaner groups.

The project will analyse both the mechanics and the effects of these developments by studying policy documents, statistical information about university populations, legal cases (such as those relating to academic dismissals), and representations of universities in both social media and traditional news outlets. Staff and students in all four countries will also be participating in the project, either as co-researchers or interviewees.

“The insights that this will generate could be powerful tools for academic managers, student unions and professionals,” Dillabough said. “They are likely to be on the front line when it comes to defending universities’ role as servants of the public good – and they are also likely to influence and instigate policy reforms that will prevent further negative effects.”

Further information about the project, including initial publications and information about the project’s opening seminar series, can be found on the project website. Follow on Twitter: @UniCrisis.

All images reproduced using a Shutterstock standard image licence.

Credits : Gokce Atik / Shutterstock.com; Gyula Bujdoso / Shutterstock.com.