The (imaginary) trip to the zoo that measures how children think about thinking

A simple game in which children plan feeding time at an imaginary zoo could significantly improve how we measure young people’s metacognition – the all-important ability to ‘think about thinking’.

The ‘Zoo Task’ has been developed by researchers at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge and at Virginia Commonwealth University, and was recently trialled with over 200 children in the United States. The results, reported in the journal, Psychological Assessment, suggest that it could fill a significant gap in the range of tools currently available to assess metacognitive skills, which are essential for success at school and in the workplace.

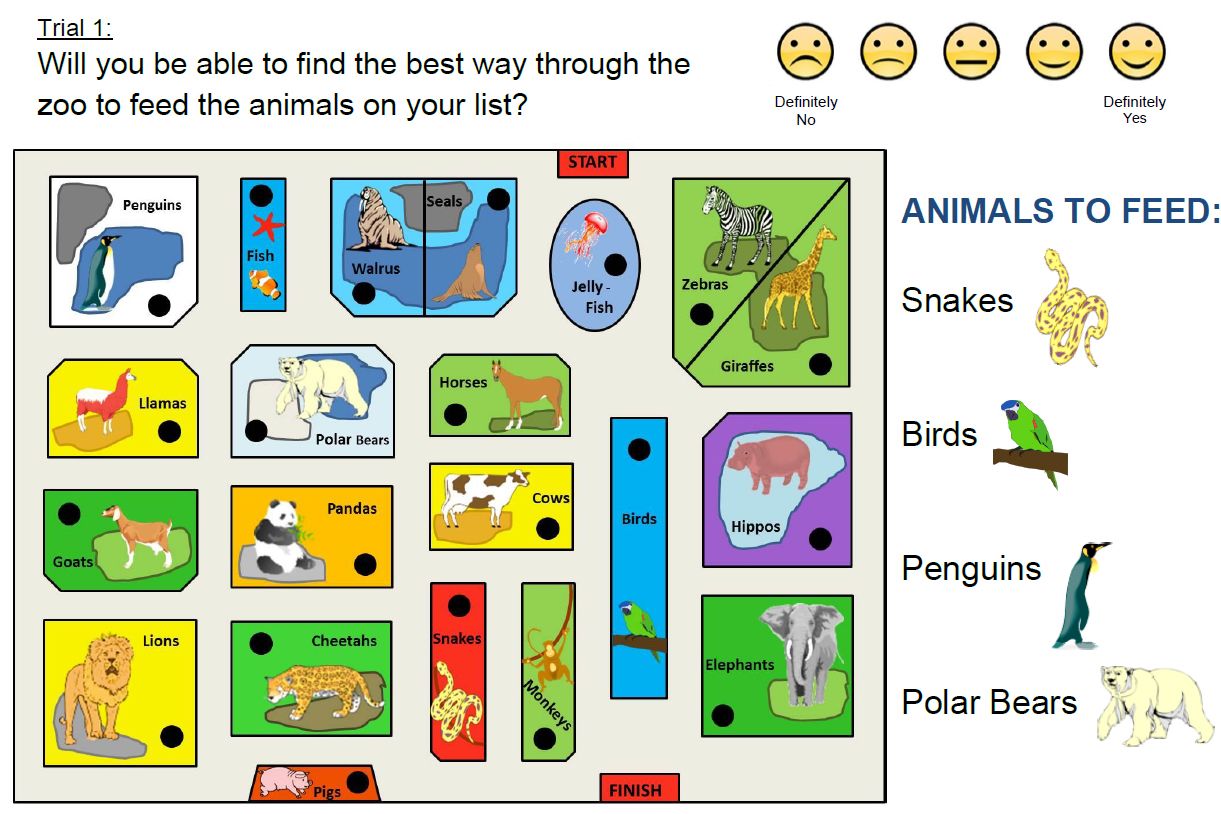

A sample exercise from The Zoo Task

A sample exercise from The Zoo Task

Metacognition has been described as the ability to understand how to think or learn. It refers to a cluster of foundational cognitive processes which underpin other essential thinking skills, such as decision-making, problem-solving, memorising, and even learning itself. For example: when revising for an exam, a student will rely on metacognitive evaluation to make effective judgements about which subject areas they need to work on most; and metacognitive control to make the effort to stay focused and avoid distractions.

Being able to measure these skills accurately is essential if we want to maximise their development during a person’s education and upbringing. While some excellent tools exist for this purpose, however, assessing metacognition efficiently, consistently and at scale is challenging.

It could easily be adapted to suit older children or adolescents – groups for whom there are currently real gaps in our knowledge

Michelle Ellefson

Many standard approaches, for example, only measure one specific metacognitive skill. The tasks used vary across age groups, and no robust tool has been devised to measure metacognitive development during the critical transition from early to late childhood. Many tools are also often time-consuming, which makes it difficult to assess large cohorts of students.

Potentially, the Zoo Task could address several of these shortcomings. Dr Michelle Ellefson, Reader in Cognitive Science at the Faculty of Education, said: “One of its big advantages is that it can be delivered by a teacher and doesn’t take much time. It could help us to study metacognition in large samples, and could easily be adapted to suit older children or adolescents – groups for whom there are currently real gaps in our knowledge.”

The task is a planning game, in which participants are given a map of a zoo, and a sequence of animals which need to be fed. They then have to draw the shortest possible route touching each animal’s designated feeding point while sticking to the zoo’s paths, before heading to the finish line.

Participants complete the exercise three times, each involving a longer list of animals. Before and after each turn, they are asked how confident they feel about finding the best route through the zoo.

We assess metacognitive control by checking for evidence of a strategy, and for any backtracking if they change their minds part-way through

Jwalin Patel

Researchers then code the completed maps in detail. As well as assessing whether a child found the best route and whether this matched their own confidence judgement, they also analyse other aspects of how they tackled the problem in order to provide a more comprehensive picture of their metacognitive skills.

“We measure how well children evaluate their own problem-solving skills and the metacognitive skills that underpin this,” said Jwalin Patel, who contributed to the study as part of his doctoral research at the Faculty of Education. “We also look for signs of metacognitive monitoring – like whether they have stuck to the rules of the game itself. In addition, we assess children’s metacognitive control by checking for evidence of a strategy, and for any backtracking if they change their minds part-way through.”

The newly-published paper reports an evaluation of the task’s effectiveness which was carried out with 204 children aged 8 to 10 years. All of the participants were from elementary schools in high-poverty, urban areas in the eastern United States.

Alongside the Zoo Task itself, participants were asked to complete a standard metamemory test, in which they were shown two sequences of 24 pairs of images with a break in between. The children had to identify which pairs in the second sequence had appeared in the first, and to say how confident they were about their answers.

The researchers examined how far the measures from both tasks correlated with one another. They also examined whether the metrics from the Zoo Task were associated with the results from other assessments of the children’s key thinking skills, to which metacognition is foundational. Finally, the measures were cross-referred with various academic test scores.

Zoo Task Correlations with the Metamemory Task Metrics as well as Executive Functions, Academic Achievement, Growth Mindset and General Cognitive Ability

Zoo Task Correlations with the Metamemory Task Metrics as well as Executive Functions, Academic Achievement, Growth Mindset and General Cognitive Ability

Overall, there was some limited correlation between the results of the Zoo Task and those captured by the metamemory exercise – a finding which partly reflects the limited scope and different measures used in the latter. The researchers did find, however, that the results of the Zoo Task corresponded closely to the other tests of cognitive ability.

For example: there were strong correlations between the metacognitive monitoring levels charted in the Zoo Task and measures of the children’s working memory. Similarly, strong associations were found between the metrics for metacognitive control and their reading comprehension and science reasoning skills.

Dr Maria Tsapali, lecturer in Education and Psychology at the Faculty of Education, said: “Overall, the trial results indicate that the Zoo Task is doing what we would expect. Given how much easier it is to deliver, this suggests that it has the potential to be a key tool that will help us to understand more about the cognitive processes that underpin students’ learning.”

In an apparent endorsement of this point, an online preprint of the research which was released to little fanfare has already been downloaded more than 600 times. “The attention this is getting suggests that it really is meeting a significant research need,” Ellefson said.

Further information about the Zoo Task is available here.

Images used in this story (starting at top)

1. Detail from Zoo Task booklet, reproduced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

2. ibid.

3. Psychological Assessment