ARCHIVE: This material is no longer maintained and should be viewed for reference only

Play specialists publish resources to take the fear out of taking a COVID swab

Read the full story here

Faculty research partner CAMFED awarded 2020 Yidan Prize for Education Development

Read the full story here.

Researchers launch live experiment to imagine the post-pandemic university

Read the full story here.

‘Thinking with your hands’ levels playing field for disadvantaged learners in STEM

Read the full story here.

Schools wanted to join study of wellbeing and learning in the ‘new normal’

Read the full story here.

Faculty member Anna Vignoles appointed as Director of the Leverhulme Trust

Read the full story here.

Sign up for free September webinars on The Way We Play

Full story and booking information here.

Profile: Catherine Ward

Read the full interview here.

Children’s fiction on terror is leading a youth ‘write-back’ against post-9/11 paranoia

Read the full story here.

How fairytales helped to break the gender binary in the playground

Read the full interview here.

Faculty researchers to play role in major initiative to help solve UK ‘productivity puzzle’

Read the full story here.

Profile: Gordon Harold

He told us a little about himself, the importance and challenges of this exciting research field, and how it may develop in his new Cambridge role.

Read the full interview here

Resister boys and modern girls: Academic achievement is influenced by how pupils do gender at school

Lockdown learning at the Faculty: Kristi Nourie

PhD student Kristi Nourie was supposed to be heading to Kansas for fieldwork when lockdown happened. Instead, she has spent the past few months working in her attic. But as she explained in a recent interview, there have been positive sides to the experience – as more talks and lectures have become available online and the Faculty has devised new ways to support students during teaching sessions on Zoom.

Read the full interview here.

Opening schools – and keeping them open – should be prioritised by Government, report says

Socio-economic status predicts UK boys’ development of essential thinking skills

Mixed early progress highlights need for sustained support for pupils with English as an additional language

Playtime with dad may improve children’s self-control

(Image credit: Family Equality via Flickr)

Thinking about undergraduate study in Education? Book now for our online Q&A!

Senior academic promotions

Promoted to Professor: Ricardo Sabates Aysa.

Promoted to Reader: Sara Baker and Zoe Jaques.

Promoted to Senior Lecturer: Karen Forbes and Bill Nicholl.

Warmest congratulations to all!

Trainee teachers praised for ‘stepping up during lockdown’ at year-end celebrations

Lockdown Learning at the Faculty: Tiong Ngee Derk

A look back at this year’s Early Primary PGCE course

For more information about the Primary PGCE course at the Faculty of Education, visit: https://www.educ.cam.ac.uk/courses/pgce/primary/

New module on educational dialogue for practitioners – apply by 3 July

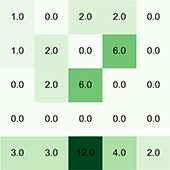

Estimating learning loss by looking at time away from school during grade transition in Ghana

Across the world, countries are facing unprecedented and changing times in trying to support the education of millions of children outside of schools. Several methods for reaching children at distance have been implemented in diverse countries, ranging from the use of radio and television in locations of limited internet penetration to full online provision for the better resourced schools. The use of off-line educational resources has also been central to delivering education to the most marginalised students, whether this is with self-instructional printed based materials to supplement textbooks, or exercise books. How much children will learn during this time remains unknown, although it is expected that the poorest will be hit the hardest.

- Children who did not have books or reading material at home, or access to reading activities, had a learning loss equivalent to 100% of the previous learning gain. Those who had these only experienced around 58% learning loss.

- Children who never asked adults for help in the household when they did not understand things at school had over 90% learning loss. Those children who did seek support had a learning loss of only 34%.

- Children who responded that they were not given enough time to study and review at home had a learning loss of 81%. Children who were given this time had a learning loss of 65%.

- Children who lived in a household without a mobile phone or tv had a learning loss between 80 to 90%. Those with these assets had a learning loss of only 40 to 50%.

- There are no differences in relative learning losses for children living in households which had access to radio.

Surging numbers of first-generation learners at risk of being left behind in education systems worldwide

School segregation by wealth is creating unequal learning outcomes for children in the Global South

The University of Cambridge-led study shows that children from the very poorest families, in what are already some of the lowest-income countries in the world, consistently perform worse in basic literacy and numeracy tests than those from more affluent backgrounds.

The overwhelming reason, the study found, is that poorer children are disproportionately clustered in the lowest-quality schools, which often lack even basic resources – such as textbooks, electricity, or toilets.

The researchers say that there is an urgent need to ‘raise the floor’ in global education, by focusing both national-level efforts and international aid on students from the most disadvantaged communities.

Institutions like the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) and the World Bank have long referred to a ‘learning crisis’ in the Global South. While growing numbers of children in low-income countries now attend school compared with previous generations, many still lack basic literacy or numeracy skills.

Until now, most analyses have looked at the factors that explain low learning outcomes in general, rather than differentiating between groups of children. But the new study suggests that there is a huge gulf between the quality of education that children from the poorest families receive compared with wealthier children, and that this is directly linked to their ability to read, write, add, or subtract, by Grade 6.

Dr Rob Gruijters, from the Research for Equitable Access and Learning (REAL) Centre, at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge, who led the research, said: “There is a high level of social segregation in many of these countries’ education systems. The pattern is similar to the UK, where rich children tend to go to better-resourced schools. But the differences in school quality are much more pronounced, and they are strongly linked to family background”

“Global reporting on the learning crisis often pays little attention to these inequalities, focusing instead on average differences between countries. But if we really want to fix things, there needs to be a commitment not only to investing in education, but to raising the floor: to ensuring that every school has a minimum level of support, in staffing, training, and resources.”

The study analysed data from the Programme for the Analysis of Education Systems (PASEC), a survey managed by the association of education ministries in francophone Africa. The survey assessed more than 30,000 Grade 6 students in more than 1,800 schools in 10 countries: Benin, Burundi, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Congo (Brazzaville), Ivory Coast, Niger, Senegal and Togo. All 10 have ‘received scant attention’ in previous analyses of the learning crisis, the study says.

The data provides the pupils’ scores in basic maths and reading tests. The researchers cross-referred this with additional information about their socio-economic backgrounds, their health, and the quality of their schools; dividing each country’s sample group into fifths based on their families’ relative wealth.

Overall, pupils from the poorest 20% of families consistently performed worst in the tests, while those children who – although often poor by international standards – fell into the wealthiest 20%, consistently had the highest test scores. Poorer students also tended to fail to reach PASEC’s Grade 6 ‘proficiency threshold’, meaning that by the time they leave primary school, many still struggle with basic sums and reading.

The researchers then explored possible reasons why this link between household wealth and performance exists. They found that differences in the quality of schooling explained almost the entire learning gap between poor and wealthier children.

Children from disadvantaged backgrounds were consistently found to be clustered in educational settings that scored low for school quality in the dataset – meaning that teachers’ own education levels were often poor, classrooms overcrowded, and critical resources and facilities, from textbooks to running water, often unavailable. Wealthier children, on the other hand, were much more likely to attend better-resourced private schools.

Importantly, in cases where children from the wealthiest 20% and poorest 20% of families attended the same school, there was almost no difference in their test results.

“The problem is that most of them are not attending the same schools, and that’s why we are seeing these learning gaps" said Dr Julia Behrman of Northwestern University, who co-authored the study. “Wealthier children learn more largely because they are going to better schools, with better resources.”

The researchers say that their assessment of the impact of socioeconomic status on learning outcomes is almost certainly conservative, as the PASEC data only covers children who reach Grade 6. In countries like Burkina Faso, Niger and Chad, where fewer than half of all children finish primary school and many never attend, the poorest children face a ‘double hurdle’: first, getting to school; and second, finding a school that is sufficiently equipped to give them a basic education.

The study therefore argues that policy initiatives and aid efforts aimed at solving the global learning crisis should focus on equalising access to learning opportunities for all children.

“One silver lining is that our research emphasises there is nothing inherent in being poor that stops children from learning,” Gruijters added. “Give them a better place to learn, with better resources, and they can do just as well as children from the wealthiest end of the scale.”

Two Faculty members scoop CUSU teaching awards

The awards celebrate outstanding teaching and student support across Cambridge and its Colleges, and provide a unique opportunity for students to nominate and recognise the contributions that staff have made to their time at Cambridge. More than 500 students put forward nominations this year. James and Riikka both received their awards during a vintage year for the Faculty, which had four short-listed staff in all, and a further 17 long-listed members.

Riikka, who won the award for Postgraduate Supervisor, said: “What motivates me most about my work with my postgraduate students is that they always bring new insights into my research group, and they are one of the greatest pathways through which I can contribute to a positive impact on the world, by helping them develop the tools to make a difference. It was really heart-warming to have my work recognised in this way, especially as this award is student-led, making it extra special to me. The online ceremony CUSU had created was fabulous, and it was so lovely being able to share it with my wonderful children, who have so often during this lockdown had to patiently wait while I attend to my students!”

James, who won in the ‘Lecturer’ category, said: “It really is about the most wonderful professional thing that has happened to me since I started working here many years ago. I’ve always felt that I worked for the students, rather than the University, which is why it matters so much.”

Further details about the awards are available from the CUSU website. You can play back the awards ceremony, and see what James’ and Riikka’s students had to say, via YouTube here.

“Now more than ever is a good time to take a step back, to reflect and reconsider”. Cambridge Quaranchats creator Simone Eringfeld on studying for three degrees, and the making of her lockdown podcast.

Children must be free to play with friends to ease stress of lockdown, Ministers told

Government ministers are being urged by an expert panel to prioritise children’s play and socialising over formal learning as the UK’s Coronavirus lockdown measures ease, to reduce the impact on wellbeing and mental health.

Among several recommendations published today, the panel, led by child mental health experts at the Universities of Sussex, Cambridge and Reading, say that children must be given ample opportunity for play and interaction with their peers in order to avert a nationwide mental health crisis.

The panel of psychologists, psychiatrists, and other academics have also written to senior ministers, strongly recommending that small gatherings of children for outdoor play should be permitted as soon as it is safe to do so, as one of the first steps in loosening the lockdown.

Re-opened schools should ensure that all children have opportunity to play and interact with their peers each day and throughout the school day, they add.

Sam Cartwright-Hatton, Professor of Clinical Child Psychology at the University of Sussex, said: “All the research indicates that children’s emotional health is suffering in the lockdown and it seems likely that this suffering will, in many cases, continue into the long term. We are urging ministers and policymakers to ensure that children are afforded substantial, and if possible enhanced, access to high-quality play opportunities as soon as possible.”

Dr Jenny Gibson, Senior Lecturer in Psychology and Education at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge said: “It’s easy to dismiss play as unimportant, but for children, playing with friends and classmates has a very significant impact on their social development. Critically, it is an important way of working through emotions and will therefore be one of the principal ways in which they cope with the isolating effects of the lockdown.”

“For that reason, it’s important that whatever steps are taken to ease social distancing restrictions, children are given time and space to play with friends. My own research suggests that social play skills are directly related both to children’s social-emotional adjustment and their academic achievement, so it is a concern that this is something that has been missing from many children’s lives for a number of weeks.”

The authors formed their recommendations following a review of relevant academic literature which confirmed the harmful impact of isolation on children and the alleviating benefits of play. One of the most striking findings came from a study examining parental reports of their children’s mental health following social distancing measures in countries affected by previous pandemics. This found that children who experience quarantine or social isolation measures were five times more likely to require mental health service input than those who did not.

The therapeutic benefits of play on child mental health have been shown in studies of children in war zones and survivors of Romanian orphanages.

Recent polling data shows that around two-thirds of primary school children are currently feeling lonely – an increase of approximately 50% compared with normal levels.

Dr Kathryn Lester, Senior Lecturer in Developmental Psychology at the University of Sussex, said: “Although many children may be spending more time playing during lockdown than usual, they may currently have a play deficit because the physical and social restrictions in place deprive them of the chance to play with their peers. We know that play with peers is critically important for children’s development. Play has substantial benefits for children’s emotional wellbeing especially during periods of anxiety and stress. It provides a sense of control, it helps children make sense of things they might be struggling to understand, and importantly it makes children happy.”

Helen Dodd, Professor of Child Psychology at the University of Reading, said: “Returning to school after a long period at home will be challenging for lots of children. It will be especially challenging if they are expected to remain 2 metres away from their friends. It is vital that this is recognised and that schools are given the time and resources necessary to support the transition carefully, with children’s wellbeing in mind. We ask that, once it is safe to do so, the loosening of lockdown is done in a way that allows children to play with their peers, without social distancing, as soon as possible. This may mean that close play is only permitted in pairs or small groups or within social bubbles that allow repeated mixing with a small number of contacts."

PGCE trainee launches fundraising campaign to support home learning for vulnerable families

A PGCE trainee at the Faculty of Education has launched a fundraising campaign to support home learning for children from refugee, migrant and asylum seeker families.

Sadhia Islam, who is currently training on the Faculty’s Primary PGCE course, is aiming to raise £1,000 to provide home learning kits and individual online access to learning to children from vulnerable families in her home city of Norwich. She is organising the initiative through New Routes, a social and cultural integration charity. Donations, no matter how small, would be very welcome and can be made now through a dedicated Just Giving page.

Sadhia, who is 22, has been volunteering for the charity for the past two years. Since the lockdown began, she has been helping to deliver online classes that give children from refugee, migrant and asylum seeker families extra learning support, supplementing the home learning arrangements provided by their school. These have proven hugely popular with parents, in particular because their children often have English as an additional language.

Worryingly, many of the children involved lack even basic resources, like pencils or exercise books, with which to do their home learning. With support from the Faculty, and one of its suppliers, the Cambridge-based firm, Landmark Office, Sadhia has secured access to low-cost items that will go into home-learning kits for her pupils. The children will receive equipment like stationery, exercise books, mini-whiteboards so that they can share ideas with their teacher during the Zoom sessions, and simple school maths kits.

“These supplies will include essential stationery resources to facilitate their home learning, and we also hope to give some children who need them electronic devices such as tablets,” Sadhia said. “As well as helping them, we want to provide a level of reassurance for their parents as well, many of whom are worried about their children’s learning amid all this uncertainty.”

Donations to the fundraising campaign can be made, entirely anonymously if preferred, through the Just Giving page. Further information about New Routes Integration is available here.

Study on regional higher education in Latin America wins best dissertation award

“I wanted to know what this regional system really was – how to analyse something without knowing what it is, where it came from and why?”

A study of the process of building a region-wide higher education system in Latin America, undertaken by Faculty member Dr Aliandra Barlete for her PhD, has won an award from the Comparative and International Education Society (CIES).

The research, which explored higher education system-building across the ‘Mercosur’ trade bloc in South America, was recently named Best Dissertation of 2020 by the CIES Higher Education Special Interest Group

Ali is a Faculty researcher who studied for her PhD within the Culture, Politics and Global Justice research group. Here, she discusses her examination of Mercosur, the relationship between education systems and their regional context, and where she is taking her research next.

Higher education was part and parcel to Mercosur’s development – but even though I am from Brazil I rarely heard much about it

I am from the southernmost part of Brazil, near the ‘Pampas’ – which is a good place to study Mercosur, a South American trade bloc that comprises Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and (currently suspended) Venezuela, plus several associate members. For the research, I could get a lift to the border from my family home and take the bus to Buenos Aries or to Mercosur’s headquarters in Montevideo.

Mercosur was established in 1991, at a time when regions across the world were trying to make new agreements as the Cold War came to an end. There’s a story that Jean Monnet, one of the architects of the European Union, said that if he was to start the EU again, he would begin with education. That inspired the policy-makers behind Mercosur to push for the creation of a defined regional education sector (SEM). Part of the logic is that if you need qualified workers who can transit between different parts of the bloc, each country has to recognise the other’s qualifications. At the same time, education is a transmitter of cultural values, believed to ‘glue’ the Mercosur region together.

I wanted to study the relationship between Mercosur and SEM as its education project, how one related to the other as they grew together from 1991, with a focus on the overall effect on higher education policies. Interestingly, despite being a Brazilian citizen, I had not encountered it very much.

My supervisors, Professor Susan Robertson, (currently Head of Faculty) and Professor Roger Dale, have done a lot of work on region-building and education.

They argue that an educational region can only exist in relationship to the wider regional structures of which it is a part. So, for example, the Bologna Process in Europe (the system by which higher education is harmonised across Europe) must be considered in relationship to the EU, even if Bologna emerged independently.

I started my project trying to apply that thinking to Mercosur: when I left for my pilot study, I had a beautifully-prepared series of questions which I wanted to ask people working in higher education in Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay and Brazil. But nothing seemed to make sense. Some said Mercosur and its education sector were a strongly coherent region, others thought it was a waste of time to research it.

So we decided to change the direction of my project. The question became what exactly is this sector? I wanted to know what this regional system really was – how to analyse something without knowing what it is, where it came from and why?” I did this by tracing the history of Mercosur’s higher education region-building from the early days of the trade bloc in May 1991, through to more recent times, navigating over almost 30 years of history.

Everyone considers Mercosur from the perspective of national gain

The member states are all trying to get different things from it. If you look at higher education, in 1991 Paraguay was leaving dictatorship and needed new regulations and structures to be put in place. Similarly, Uruguay’s education system was very limited: the national higher education law was largely the law of the only public institution in the country. On the other hand, Brazil has hundreds of universities and a complete Higher Education system. So, for Paraguay and Uruguay, the creation of a regional system meant the reshaping of their national higher education system. In many ways, they are ‘region-takers’. For Brazil and Argentina, as ‘region-makers’, the advantages were more about positioning themselves as regional leaders and contributing to it with resources and ideas.

The region as a whole works based on different national capacities and interests. And it has been weakened further by explosive politics: Mercosur is a body which spends a lot of time managing the relationship amongst its member states – Venezuela is not a full member at the moment, for example.

This means that Mercosur has weak legitimacy, which has played out in efforts to build a higher education region.

In essence, the things that the Mercosur Education Sector promotes are not absorbed consistently at the national level. Everyone ends up participating in initiatives according to their political will and their capacity. The accreditation project is a good example of this: it worked and became successful after the member states built on their national differences, rather than on their similarities.

In Brazil, there is a law that if you have a degree from another country, your degree is only valid if a Brazilian public university approves it. So regardless of the Mercosur programme, if you wanted your degree to be valid in Brazil, you had to go through that process. By contrast, Argentina recognises the accreditation system and makes every effort to implement it. In Paraguay and Uruguay did not have the structure in place, so had to create them first. Even if the members supported the idea of regional accreditations, astonishingly, it took them 10 years to enable its implementation! So there is a broad mismatch in how the decisions are made and then implemented.

Those responsible for SEM are passionate about it, but its visibility is low

It was clear that the people trying to make Mercosur higher education happen system-wide work hard to make it happen and are devoted to its mission. But a lot of their work rarely translates into effective initiatives on the ground due to low political support, and SEM’s visibility remains quite low - with the exception of Argentina. Across Mercosur, there are millions of students – but only a few hundred have taken advantage of the opportunities for mobility that the accreditation system is supposed to make possible.

The region continues to struggle

The latest blow is Brazil leaving SEM altogether (in November 2019) which again speaks to this focus on national political decisions rather than wider regional judgements: the argument was the lack of efficiency and results, despite the investment of national funds.

Overall, the study demonstrates the relational connections between political and economic regions and HE regions also happens in Mercosur. However, they are largely influenced by the political leaders of the time, and by external bodies, such as the Ibero-American States Educational Organisation (OEI) and the EU. These are the ones that grant the necessary legitimacy, as well as funds and capacity to carry out the work – not Mercosur, as the region which hosts SEM.

I’m now taking a teaching position at the University of Edinburgh

Since finishing my PhD, I have been supervising undergraduates for the Faculty, and working as a consultant for UNESCO’s Higher Education Office in Latin America (IESALC). I have recently taken a Teaching Fellow position at the University of Edinburgh’s Moray House School of Education and Sport. It is an exciting opportunity and I am really looking forward to working with students and supporting them the best way I can.

Multilingual families asked to join nationwide study of languages under lockdown

Families who speak more than one language are being invited to join a UK-Irish study to understand how school closures could affect multilingual children’s education and language use during the coronavirus lockdown.

The research is being carried out by a team from several different universities and language associations, including members of the Faculty of Education. Although part of the aim is to gather evidence about how the closures may affect multilingual children’s English language development, the researchers believe that it may also highlight other issues – including the possibility that some children may benefit from increased exposure to their home language.

Approximately 300 different languages are spoken in the UK. According to the Government’s School Census, more than one fifth of children speak ‘English as an additional language’ (EAL) – and another language at home.

While some teachers and parents are concerned that these children could be at risk of missing out on education while mass home-schooling continues, there is little evidence available to show how multilingual families will respond to the lockdown, or what the results for EAL children will be.

“At the moment, we don’t have a good picture of multilingual families’ attitudes towards language in general, so it’s difficult to understand what impact the lockdown will have,” Professor Ludovica Serratrice, Director of the Centre for Literacy and Multilingualism at the University of Reading, said.

“So much of this is shaped by parents’ feelings and beliefs. Families might, for example, change their policy on what language is spoken in the home while schools are closed. We want to understand what is driving their approach, and what this might mean for children’s education.”

Co-researcher Dr Elspeth Wilson, from the Faculty of Education at the University of Cambridge, and a part of the Cambridge Bilingualism Network, added: “This is clearly a situation in which young people’s exposure to language is changing massively, but it’s not simply about English language development. Spending more time with their home language could have a number of effects, including possible benefits. By finding out more about this, we should be able to provide useful information both for education professionals, and multilingual families themselves.”

The researchers are inviting multilingual families to take part in an online survey. Any UK or Irish-based family with at least one child under 18, who are living together during the lockdown period and speak a language other than English, can participate. All contributions will be anonymous.

Participants will be asked to complete online questionnaires at three different stages: during the closures, when schools reopen, and in April 2021. They will also be invited to participate in an optional interview. Through this, the researchers hope to document changes in their patterns of language use.

Some parents and teachers have expressed concerns that EAL children’s English language development may be negatively affected by the closures. Before the COVID-19 outbreak, about 30% of children’s time was typically spent in childcare, school, or extracurricular activities. For some EAL children, this would have been their main experience of an English-speaking environment. Researchers have also suggested that many teachers who are used to delivering lessons in mixed, multilingual classrooms may struggle to adapt their approach to online teaching.

On the other hand, the drawbacks for EAL pupils may have been exaggerated. Attainment data released by the Department of Education has shown that these pupils often perform well at school and may even outperform their non-EAL peers – although this generalised data often masks significant regional and demographic discrepancies.

Researchers believe that the real impact for EAL pupils is therefore likely to vary across different communities, ages and groups. Some may benefit from concentrated exposure to their home language – and it could provide them with a stronger foundation for developing their English, as well as for learning other languages, when they return to school.

In addition, the research team point out that languages act as vehicles for identity, and that a strengthened relationship with their home language may deepen EAL pupils’ connection with their relatives, their community, and their cultural heritage.

“There is an argument that for some children there could be positive gains, particularly if the situation doesn’t go on for too long,” Dr Wilson said. “More contact with their home language may actually improve their interest in language learning, and it could lead to stronger relationships at home and in their wider family. For many, speaking more than one language is a wonderful gift and resource. This may be a great opportunity for them to embrace that multilingualism and share it with family and friends.”

The participating institutions are the Universities of Reading, Cambridge, Oxford, University College London, the National Association for Language Development in the Curriculum, Mother Tongues Ireland and We Live Languages. Further information is available at: https://research.reading.ac.uk/celm/research/2343/

More information about current research into multilingualism is also available on the Cambridge Bilingualism Network’s website: www.wespeakmulti.com

Zoom reunion captures powerful experiences of MPhil alumni amid coronavirus outbreak

While Faculty members may be locked down all over the world, students from last year’s MPhil in Education, Globalisation and International Development didn’t let that stop them from holding a virtual reunion by Zoom earlier this month! The gathering, which involved participants from six continents, provided some fascinating insights, and powerful stories, about how these colleagues’ careers have changed direction dramatically, within a few short weeks, as a result of COVID-19. Here, former student Rachel Zink provides a brief overview of their experiences:

This month, the EGID 2018-2019 MPhil students held a virtual reunion over Zoom, coming together from across 6 different continents. Despite the various time zones, 17 members of the cohort were able to join the reunion, creating a virtual room full of smiling faces and laughter. Most of the conversation focused on giving personal updates and sharing how COVID-19 has impacted our work, communities and countries, as this global health crisis has affected everyone in some way.

Some of us are now working from home or had to return to their home countries. British resident Caroline Breeden has been working on English language learning programmes in Mexico City, but she is now working remotely from the UK. For others, work has been cancelled or postponed indefinitely due to the crisis, especially those working in international education programmes. Bethan Morris-Tran and I were within a few days of leaving for Japan to facilitate an empowerment programme in schools when the Japanese government closed down schools nationally. Originally Morris-Tran envisioned she would be helping students build public speaking skills, but instead she is now helping fight the public health crisis by working the frontlines at a hospital.

Those who went into education in emergency zones, like Siddharth Pillai working in Afghanistan, are in environments where ‘emergency education’ now includes delivering education during a pandemic. Pillai suddenly finds himself advocating for Afghani students to receive free mobile data to empower their online learning, “Telecom service providers in Afghanistan shall be doing a world of good for students and teachers if they could grant free internet data to access select educational sites.” His recently published article can be found here.

Worldwide school closures not only affects teaching and learning, but also research conducted within schools as well. Although Judith Hannam has found the pandemic to inhibit her ability to collect data, it also brings opportunities for positive change, “It is forcing all of us to be more creative and possibly to be more able to expect the unexpected.” Those, like Jong-Woo Lim who are working from a policy level, are now creating and revising educational policies to respond to COVID-19 and address the needs of our rapidly changing world.

While for some their workload has increased, others are forced to slow down from their busy lives, like one of our members who has been self-isolating with symptoms of COVID-19. Others are also using this time for writing or revising their MPhil thesis for publication. Many have also started online learning or taking free online classes, such as quantitative data analysis and human rights courses.

While COVID-19 has impacted our cohort in a wide variety of ways, we all seem to be reflecting on the essential role education plays in our daily lives, whether it takes place within classrooms or within homes, or whether it is teaching a group of children about germs or educating entire communities on public health safety. While schools stand dormant from temporary closures, we remember what a privilege it is to have access to schools and what it means for those who do not.

Although this pandemic has disrupted many aspects of our lives, it can also inspire positive changes, opportunities to help in unexpected ways, and joyful moments—like a virtual reunion. No matter where our group is in the world, we continue to support each other and learn from one another. Whether we are in Cambridge, our hometowns or in an unexpected place, we are still collaborating, exchanging ideas and sharing practices. We are still celebrating each other’s achievements, life events, and during challenging times like this, we are still encouraging one another. The bond that originated in Cambridge continues to transcend borders and have a far-reaching impact all over the world.

(Re)Discovering Children’s Nonfiction in lockdown

With schools closed, millions of parents are having to adapt to the considerable challenges of home schooling – something that, according to recent research by the Sutton Trust, most find a daunting prospect.

But if worksheets and video learning are wearing you down, there are alternative ways to keep young people engaged with education. Here, Karen Coats, Director of the Centre for Research in Children’s Literature at Cambridge, explains why the relatively unsung world of children’s non-fiction is a rich resource just waiting for children (and their parents) to rediscover it.

If you’re a parent, you’ve probably been bombarded with advice and tips to keep your kids occupied and on track academically during this time of public isolation. And I’d be willing to bet that most of you are frustrated and maybe even frazzled as you struggle to be an employee learning to work remotely, a parent who hasn’t spent the long daylight hours alone with your kids for a while, and a personal tutor who never learned any techniques for teaching.

But you know what you used to be an expert in? Learning stuff you were interested in. Maybe you feel as though you weren’t a great student in school, but back when you wanted to build a slingshot, or tie complicated knots, or make an origami crane, you pursued your interest with diligence; you tracked down source materials, ran experiments, and persisted through failures until you were satisfied or bored. And when boredom overtook that project, you sought out another. This is most often the pattern of childhood interests, driven by a brain hungry for novelty to drive its growth.

This is where the wonderful world of children’s nonfiction literature plays a special role. While children’s novels get most of the attention (and awards), children’s nonfiction has come into its own in recent years, offering everything from cookbooks, to how-to manuals, to histories and biographies that children and teens actually want to read.

Think about it: unlike textbooks, trade books have no guaranteed market. To sell well, they have to focus on subjects young people will find interesting, and in entertaining and accessible ways. In other words, they must be designed for pleasure reading. Of course, that doesn’t mean they can’t enhance the curriculum, or spawn new ideas for revision. So, if worksheets and video lectures are getting you and your kids down, try some of these. Best get copies for yourself as well – you’re going to want to read these with your kids. And remember—this is reading for pleasure, so no quizzes: just sharing what surprises and delights you.

It’s not just knowing your children, but being aware of some concerns that are tied to their developmental age, that are two keys to choosing good nonfiction. It’s often good to follow, rather than lead, by making selections based on subjects that are catching their attention at the moment. That may be very different from what they are learning about at school. It may be something that’s not in the national curriculum at all, or it may be something that they weren’t able to go into more deeply before the teacher moved on.

While lists and reviews abound online, here are some of my all-time favorites for readers of different ages:

Young readers

For the little ones, pictures are everything. Don’t worry if they aren’t interested in the text—let them browse through the books and ask questions, which they will do sometimes simply by pointing or lingering over a picture rather than forming words. Linger silently with them, allowing them to enjoy or puzzle over the pictures. Steve Jenkins’ Actual Size and Prehistoric Actual Size are guaranteed kid-pleasers. Children won’t be able to resist comparing the size of their hands, eyes, and noses with the stunning, life-sized collage representations of these parts in the world’s largest and smallest critters! You may also want to check out his website, where you and your kids can find information on how his books are made from inspiration to completion. Have some craft paper available in case your kids get inspired.

Books illustrated with photographs by Nic Bishop also rank high for young browsers. He gets up close and personal with frogs, spiders, snakes, and butterflies, often using a sequence of stills to slow down the action of, say, a frog capturing its prey or a ladybird taking flight. His photographs elicit reactions ranging from disgust to delight, and encourage viewers to pay closer attention to the natural world.

Older children

In middle childhood, say around 8-13, children often develop passionate (if fleeting) obsessions. Reading and the internet have opened the whole world to them, and that’s overwhelming. Researchers have explained how focusing their attention on one thing enables them to gain a sense of mastery; they become experts as they memorize names of dinosaurs, collect all the books in a series, or immerse themselves in the French Revolution. Some kids are more hands-on, they want to learn to make things and take them apart. But there is a strong case that children at this age want a human element in their nonfiction. They are seeking how knowledge is built, who builds it, and how they might become knowledge builders themselves.

For this reason, you might direct their attention to books from the Scientists in the Field series. These books take readers beyond the facts reported in their textbooks to the behind-the-scenes stories of success and failure as scientists strive to understand and intervene in the natural world.

For children more interested in the A in STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, and Mathematics), try Joyce Sidman’s remarkably beautiful mixed media book about a woman who was an artist, scientist, and explorer at a time when those interests condemned her as a witch, The Girl Who Drew Butterflies: How Maria Merian’s Art Changed Science, or Janine Atkins’ imaginative accounts of three famous women and their daughter rendered in verse, Borrowed Names: Poems about Laura Ingalls Wilder, Madame C. J. Walker, Marie Curie and their Daughters.

Of course we mustn’t neglect aspiring athletes. Kadir Nelson’s We Are the Ship: The Story of the Negro League Baseball or Philip Hoose’s Attucks!: Oscar Robertson and the Basketball Team that Awakened a City might inspire British kids to investigate similar histories of their favorite sports and the athletes who had to struggle to gain a place on the field. These books also draw attention to the active role sports can play in making the world a more socially just place.

Another timely topic for contemporary young people is the need to sort out reliable information from the fake stuff. Ammi-Joan Paquette’s series (two so far) Two Truths and a Lie offers an opportunity for the whole family to guess which of three barely believable accounts of animals and events are true and which are cleverly crafted fictions. Dust off your research skills or learn some new ones as you enjoy these tales of the weird.

For more hands-on learners and budding architects and engineers, try The Lego Architect, by Tom Alphin, or learn the basics of computer coding with Gene Luen Yang’s Secret Coders series (okay, these aren’t nonfiction, but they do offer logic puzzles and a kid-friendly introduction to coding, so I slipped them in!)

Teens

For older readers, learning to navigate personal relationships and thinking through larger societal problems take precedence. What’s perhaps most important for teens is a frank portrait of the failures and emotions that were often part of famous people’s experiences, or of famous events. Hence a shift toward narrative nonfiction and original forms, like graphic narratives, is in order.

Turing 15 on the Road to Freedom: My Story of the 1965 Selma Voting Rights March is a richly illustrated story of a teen who marched with Martin Luther King, Jr. Although the context is American, the lessons imparted about nonviolent protests and the ability to be part of a movement that changed history are extremely relevant to today’s worldwide attention to climate change.

For a detailed look at the Manhattan Project that reads like a spy novel, you will be enthralled by Steve Sheinkin’s Bomb: The Race to Build - and Steal - the World’s Most Dangerous Weapon. In addition to creating heart-thumping suspense for a story whose outcome we already know, Sheinkin is terrific at explaining the science behind the different kinds of bombs in development.

Want a fresh look at World War I? Try Chris Duffy’s edited collection Above the Dreamless Dead: WWI in Poetry and Comics. He commissioned leading comics artists to illustrate poems by Wilfred Owen, Rupert Brook, Robert Graves, and Rudyard Kipling, among others. Different styles evoke the various emotions of soldiers as the war progressed.

Nobody does biography for young people like Deborah Heiligman. Charles and Emma: The Darwins’ Leap of Faith (Macmillan, 2011) explores how the schism between religion and science worked its way through the Darwin’s own marriage. As one review puts it: ‘Come for the science, stay for the love story.’ She also explores the loving but fraught relationship of Vincent Van Gogh and his brother Theo in Vincent and Theo: The Van Gogh Brothers. Though Heiligman writes with the style of novelist, she sticks to her ethic of not making anything up, but instead draws from letters and other primary sources to craft rich and absorbing narratives that flesh out the humanity of people whose work changed the world.

Finally, while it might be a little too fresh to consider catastrophic disasters and manmade tragedies, Don Brown’s graphic treatments of Hurricane Katrina, the Syrian Refugee crisis, and the dust bowl years in America might help some readers realize or remember that humans are resilient, that this present crisis will also pass, and that while we will make mistakes, understanding comes retrospectively, and we can take what we’ve learned to make better decisions going forward.

Whatever age your child is, whatever your child is passionate about, there’s a book for that, and it’s likely that you will rediscover a few passions of your own along the way.

(Image credit: Neeta Ling, via Flickr)

COVID-19 school closures may further widen the inequality gaps between the advantaged and the disadvantaged in Ethiopia

There are major challenges around equitable access to learning for all children during the COVID-19 crisis. Most governments have now temporarily closed schools and universities to slow the spread of the virus. As of the first week of April 2020, UNESCO reported that 1.6 billion learners (nearly 9 out of 10 children) are out of school worldwide due to the school closures. In Africa, almost all the school children and university students are affected by the pandemic as of mid-March 2020. In Ethiopia, for example, schools have been closed from 16 March 2020, and nearly 25 million pre-primary, primary, secondary, and tertiary-level learners are staying at home.

Think Local: Support for learning during COVID-19 could be found from within communities

21 Faculty members receive student-led teaching award nominations

As the name suggests, these awards rely entirely on the feedback and testimonials of students themselves and over 500 students across the university put forward nominations this year.

Of the 44 university staff members who made the final shortlist, four are based at the Faculty of Education, while a further 17 were long-listed. This is really welcome news at a time when so many of our staff are working extremely hard to ensure that teaching, learning, assessments and support can all continue under lockdown. Thank you to all our students who put suggestions forward.

The Faculty nominees are:

Short-listed: James de Winter; Arathi Sriprakash; Jo Dillabough; Riikka Hofmann.

Long-listed: Andreas Stylianides; Bill Nicholl; Carol Holliday; Elaine Wilson; Helen Demetriou; Hilary Cremin; Jennie Francis; Karen Forbes; Kristine Black-Hawkins; Mark Winterbottom; Nidhi Singal; Pam Burnard; Rachel Foster; Ricardo Sabates Aysa; Susan Robertson; Tyler Denmead; Zoe Jaques.

This year's awards ceremony will, of course, be taking place virtually. Further details can be found at: https://www.cusu.co.uk/2020/03/26/shortlist-announced-student-led-teaching-awards-2020/

New Faculty Gates Scholars announced

Two of the 2020 cohort of Gates Scholars – one of the world’s most prestigious scholarships for postgraduate students – will be studying with the Faculty of Education, it has been announced.

Morgan Healey, from the United States, and Julia Jakob, from Austria, are among 77 new scholars from 30 different countries who have just been announced by the Gates Cambridge Trust as the programme’s Class of 2020.

Gates Scholarships are awarded to academically outstanding and socially committed postgraduates. The programme was launched in 2000, with a donation to the University from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and since its inception has supported the postgraduate education of more than 1,700 scholars at Cambridge, from more than 100 different countries.

Morgan graduated with a Masters in International Education Policy from Harvard in 2019, and worked at the Harvard David Rockerfeller Centre for Latin American Studies in Brazil, where she led strategy and content redesign work on their Certificate for Early Education Leadership. Her PhD will focus on the development of a play-based parenting intervention that helps young children to develop key higher cognitive capacities (executive functions) – partly with a view to addressing gaps in early childhood programming in Brazil and elsewhere.

Julia is a graduate of the University of Vienna and has worked with refugees, teaching German as a second language. She is interested in the many different forms that accessibility barriers in education can take and the ways in which what appear to be the characteristics of individual learners – such as motivation – can sometimes be symptoms of much wider, systemic accessibility issues. Her research will focus on understanding how male refugees perceive their own identities and the relationship between this and their motivation to learn languages, with a view to making second language education more accessible and inclusive.

Stephen Toope, the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cambridge, said: “The Gates Cambridge Scholars are an outstanding group of people. They have not only demonstrated exceptional academic abilities in their fields, but have also shown a real commitment to engaging with the world – and to changing it for the better. They truly embody the values our University cherishes – excellence, a global outlook, and an aspiration to contribute to society; values that are needed more than ever at this terrible time.”

Professor Barry Everitt, Provost of the Gates Cambridge Trust, said: “The Scholars-elect fully meet the aspiration of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation’s generous and historic gift to the University of Cambridge. This year’s selection process has taken place against the background of the COVID-19 pandemic, which more than ever shows the vital need to bring together from around the world the most brilliant minds from the most diverse backgrounds to work on global challenges.

“This year’s cohort, like its predecessors, is an impressive group of individuals who have already made their mark in their academic studies and demonstrated strong leadership qualities. We are particularly delighted that we were able to offer awards to a large number of PhD scholars. We are certain that our 2020 Gates Cambridge cohort will flourish in the vibrant, international community at Cambridge and go on to make a significant impact in their fields and the wider global community.”

Further information about the scholarships programme is available here. More information about Graduate study at the Faculty can be found here.

Rethinking education in the time of COVID-19: What can we contribute as researchers?

Free-to-access study opens up insights into coding classroom dialogue

A detailed analysis of different approaches to ‘coding’ classroom talk – which includes two tools that education professionals can use or adapt for this purpose – is being made freely available online for the next few weeks.

The paper, which is free to access and download until April 28 from the journal, Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, was written by researchers from the Cambridge Educational Dialogue Research Group (CEDiR), in the Faculty of Education.

Alongside in-depth practical guidance about the many issues that need to be considered when coding classroom dialogue, it shares two open-source tools developed by the group. These can be used by any researcher or education professional to code dialogue, and through this study classroom interactions and student participation.

Interactions that support dialogue in the classroom – such as asking open questions, or encouraging shared reasoning and thinking – have been shown to have a positive impact on students’ learning. To improve our understanding of how best to apply such approaches, researchers record and then analyse interactions, which inevitably involves categorising, or ‘coding’ sections of dialogue.

The challenges of doing this effectively are, however, seldom discussed. “Published reports rarely report on the trials and tribulations involved,” the authors of the new paper point out – adding that readers could be forgiven for assuming that it is reasonably straightforward. In fact, coding dialogue is a complex process. To support anyone undertaking such a task, the paper covers various approaches and their respective pros and cons, while stressing that there is no one-size-fits-all ‘recipe’.

It highlights a number of issues to bear in mind. For example, any coding system will have limits of scope (what it can and cannot measure). The granularity of systems also varies: while many researchers prefer detailed, micro-level coding that focuses on snippets of dialogue, a wider purview will consider the often-critical context and trajectory of a classroom discussion. Any system also needs to be tested thoroughly to make it as reliable as possible – not least because classifications of dialogue are often vulnerable to being inferred, or over-interpreted.

The paper offers insights from two related systems, both developed by CEDiR researchers. The Scheme for Educational Dialogue Analysis (SEDA) was created by the paper’s lead author, Dr Sara Hennessy, and a large team of researchers in Cambridge and Mexico with British Academy funding. Among other things it strikes a balance in granularity by combining 33 coding categories for micro-analysis in partnership with a set of more general descriptors.

Importantly, SEDA has not just been used in its ‘out of the box’ form, but adapted by researchers internationally for various different analyses of classroom dialogue. It recently provided a basis for the development of the Cambridge Dialogue Analysis Scheme (CDAS), through which researchers (Howe, Hennessy, Mercer, Vrikki & Wheatley, funded by ESRC) analysed 9,000 minutes of video-recorded lessons in 48 state-funded British primary schools, to study the relationship between different dialogic approaches and student outcomes in standardised tests.

The paper shows how these tools were developed, tested, and used. In the case of CDAS, it also explores how it adapted parts of the SEDA system. For example, coding techniques originally developed within SEDA for micro-level analysis were employed at a broader level in the CDAS rating scales to capture the context and ‘classroom ethos’ in which dialogic exchanges were taking place. The multi-level coding approach has enabled some significant research insights.

The article therefore demonstrates how building on existing tools “allows researchers to shortcut the initial development process and consider how best to modify them to address new needs arising in new contexts.” As new technology continues to open up exciting possibilities in the analysis of classroom dialogue, such techniques are likely to prove increasingly important. As the authors add: “The time is ripe for researchers, practitioners and professional development leaders to explore creative and complementary new approaches for analysing and developing dialogue in classrooms, both micro-level coding and other approaches.”

Reference:

Sara Hennessy et al. ‘Coding classroom dialogue: Methodological considerations for researchers.’ Learning, Culture and Social Interaction (Vol. 25, June 2020). DOI: 10.1016/j.lcsi.2020.100404

Cambridge student wins BERA Masters Award for second year running

Our buildings are closed - but the Faculty is open!

Fortunately, the Faculty will still be very much open! From this date, we will be doing as much of our work as we can remotely.

If you are interested in finding out more about our courses or our research, please take a look at our website and do get in touch.

Current staff and students should check their email regularly for updates. The latest information about University-wide arrangements is available at: https://www.cam.ac.uk/coronavirus

Please do follow the latest public health guidance. We look forward to seeing and talking to you all soon!

New title explores different approaches to researching educational dialogue

“As a BAME trainee teacher, I worried about fitting in. I’m glad I didn’t let my fears hold me back”

Cambridge creates new Professorship in education and mental health

Allocation system is source of socio-economic divide in schools access

Global coalition needed to transform girls’ education - report

Faculty members appointed to Government advice panel

Dr Riikka Hofmann and Dr Sonia Ilie will both be part of the panel, which comprises around 50 experts from outside government (mostly academics) and the Civil Service.

The panel provides free advice to policy teams and analysts, helping them to design robust evaluations to test potential new policies, or changes to policy. TAP also provides training to civil servants on the benefits and technicalities of impact evaluations.

Since its launch in 2015, the panel has advised on 72 projects across 24 departments and public bodies, spanning policy areas including energy, adult social care, housing and family service. The members are all appointed for two years, starting from 20 February 2020.

Riikka is a Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Education, where she leads the Research Strand, 'Dialogue, Professional Change and Leadership' in the Faculty's Cambridge Educational Dialogue Research Group (CEDiR). Her research focuses on leadership and professional change in educational and medical settings.

She was selected as an expert member of the panel in at its inauguration in 2015 and has been selected to continue serving. Riikka has previously contributed to a blog post about her experiences on the panel.

"Using academics to advise on policy trial design in such a centralised systematic fashion is very innovative," she said. "As academics, we often question how much our work matters, so having an impact on policy and professional learning in the Civil Service is really rewarding. It's shown me that education research has wide benefits, and given me a valuable insight into how policy-making works, as well as new relationships."

Sonia, who is joining the Panel for the first time, is a senior research fellow at the Faculty of Education and research leader at RAND Europe, an independent not-for-profit research organisation. She researches educational inequality and runs large-sale experimental and quasi-experimental evaluations of programmes tackling the socio-economic attainment gap in schools, and inequitable access and outcomes in higher education.

You can read more about the full panel here.

More information and examples of TAP's work are available in its three year update report.

Knowledge, Power and Politics in Education

Following a successful launch at the Faculty’s post-graduate open day, applications are currently being received for the Faculty’s new full-time MPhil route in Knowledge, Power and Politics in Education.

The course presents an exciting new offering in the Faculty MPhil programme, drawing on an interdisciplinary approach to examine the dynamics shaping knowledge formation in formal, non-formal and informal education settings around the globe – from governmental structures to social movements.

Coordinated by Dr Liz Maber, the course draws on the research and expertise of colleagues across the faculty including Dr Hilary Cremin, Dr Jo-Anne Dillabough, Dr Eva Hartmann, and Prof Susan Robertson to explore fundamental questions relating to:

- the roles of education in societies;

- transnational debates about the nature of knowledge formation and its circulation;

- and the consequences for social justice.

Drawing on varied theoretical perspectives and empirical approaches, the course engages with different understandings of the education/knowledge/power nexus, its implications for societies and the interactions with major global issues including social and spatial mobility, urbanisation, sustainability, and conflict.As underlined by Prof Susan Robertson, Head of Faculty, and Professor of Sociology of Education;

Knowledge, Power, Politics has to be at the top of your list – as a course which engages in cutting edge conversations about education in ways that matter

Find further information on our MPhil Kowledge, Power and Politics in Education and how to apply for the course.

Share this story

A Jar of Teddies - Live webinar introduces learners to mathematical problem solving

'Great morning for our mathematicians in Year 8 and 9 @WorleSchool. They got involved with @maths_week by joining students all over the country to problem solve in a live webinar ran by @nrichmaths. Fantastic work!'

@WorleSchool (Twitter)

'So much problem solving and collaborative discussion among our pupils. Who would have thought estimating teddy bears could create such a buzz!'

Share this story

Faculty partnership school wins Educational Innovation award

NIS beat some seriously strong competition and won the Wenhui Award for their building of 'School-University Partnerships for Students Benefit'. Since their creation, NIS have partnered with national as well as international universities to support their graduates and recognise students’ achievements. Congratulations to Nazarbayev Intellectual Schools for their fantastic achievement and winning this award.

Share this story

PGCE 2019 off to flying start

They arrive alongside new course managers (Mark Winterbottom and Shawn Bullock) leading the secondary PGCE team. Jane Warwick and John-Mark Winstanley extend their fantastic leadership of the primary PGCE team into another year. And we’re also delighted to welcome Tabitha Millett (Art and Design – a former Cambridge PGCE student) and Daniel Moulin-Stozek (Religious Studies) to the secondary PGCE team while Kate Rigby has already made a valuable contribution to the primary team.

Since September, our trainees have been cutting their teeth in school, gradually building up their teaching in a personalised programme with their excellent school-based mentors. The level of commitment of those mentors was described by external examiners as ‘almost unique within PGCE courses nationally’.

On both primary and secondary courses, alongside and integral to their school development, Professional Studies is well underway, with trainees learning how to ‘Teach without Disruption’ from Roland Chaplain and getting stuck into behaviour for learning workshops.

And in subject studies on the secondary PGCE, our trainees have been thinking, and thinking hard, about teaching and learning in their subjects. From speed-dating workshops to a classroom crime scene, from inclusive design to engaging learners in Latin through video, and from whole class composing to preparing exhibitions of art work, our trainees have been very busy indeed. And that’s without even thinking about skateboards, lungs, and explosions in science, or the link between pie charts and trigonometry in maths!

On the PGCE Primary course, trainees have been getting to grips with understanding how children learn and the diversity of the primary curriculum, exploring the different teaching and learning approaches and practical ideas for each subject: making maps in geography, clay models in art, recreating the last supper in RE, designing pop-up books in DT, getting to grips with coding and programming in IT, launching rockets in science, teaching ball handling skills in PE, developing knowledge of children’s literature, reading comprehension and phonics in English.

All that and inspirational speakers - Dame Alison Peacock, the CEO of the Chartered College of Teaching, on ‘Why teaching is the best profession in the world’ and Morag Styles, the first Professor of Children’s Poetry for a poetry at teatime event.

Share this story

Play Well - Hopscotch Project featured in new Wellcome exhibition

Share this story

Young women writers celebrated at BBC Awards

The shortlisted writers for the Young Writers’ Award had a whole day at the BBC before the awards ceremony. During the morning, they spent some time in a studio, creating radio sound effects and working with an actor reading from Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own. Elizabeth commented, "This was an apt text choice because, not for the first time – and like the adult award – the Young Writers’ Award had an all-female shortlist this year".

Later in the day, Dr Sarah Dillon from the Faculty of English and Elizabeth led a mini seminar. This gave the young writers an opportunity to talk through Woolf’s ideas about the conditions in which women’s writing can flourish, and to discuss the radical structure and style of Woolf’s prose. Elizabeth says, "Unsurprisingly, given the wonderful qualities of their own writing, the young people impressed both of us with their insight and sensitivity in this conversation".

Virginia Woolf was passionate about enabling access for women to education, as well as to the kinds of privileged spaces of protection from everyday household worries that enable creativity to flourish. Elizabeth reflects, "As a woman academic in the midst of the complex balancing act entailed by our commitments to research, teaching, homes and children, and aware of the gender pay gap in academia, it’s easy to feel acutely how far we are, as a society, from some aspects of Woolf’s idyllic visions. It was heartening to hear these young women’s conviction that their gender constitutes no limit on their voices and their writing".

Sarah and Elizabeth enjoyed a chance to talk more informally with the shortlisted young people and their families, about their writing, their future hopes and plans, and about university applications and admissions. "Several of them spoke warmly of the role of individual teachers in prompting them to pursue their ambition to write, to practise self-discipline in establishing effective writing habits, and to submit their work to competitions such as the BBC Young Writers' Award". As the Subject Lecturer on the Secondary English PGCE, Elizabeth spends a lot of time telling the Faculty’s PGCE students about their potential to influence people’s lives, she adds, "it was wonderful to have in front of me such inspiring examples of these positive teacher influences".

Elizabeth Rawlinson-Mills is the Subject Lecturer for PGCE Secondary English. Find out more about our PGCE courses and outstanding (Ofsted) teacher education at the Faculty of Education, University of Cambridge.

Share this story

Bridging the gap between theory and practice in a complex world

A Brandon Hall Excellence Award is fiercely competitive in the field of learning. It attracts entrants from leading corporations around the world, as well as mid-market and smaller firms. This year submissions were received from 25 industries in over 30 countries. Now entering its 26th year, the Excellence Awards are the most prestigious awards program in the industry and are often referred to as the academy awards for their field.

The awards cover a range of categories including Learning and Development, Talent Management, Leadership Development, Talent Acquisition, Workforce Management and HR, Sales Performance and Corporate Initiatives.

Elaine Wilson, University Senior Lecturer in Education and EdD Programme Manager at the Faculty of Education commented 'For me this award displays the potential of the EdD to extend Cambridge’s reach into diverse fields education and learning. It provided the necessary rigor and relevance to explore grounded, creative approaches to real-world problems that have day-to-day impact across a wide range of settings. It also plays to what we do best at Cambridge - providing a nurturing environment that facilitate rich interdisciplinary connections, something many institutions talk about but few can deliver on’.

Awards are evaluated by a panel of experienced, independent industry experts, analysts and executives based upon the following criteria: fit the need, design of the program, functionality, innovation and overall measurable benefits. See the winners in all categories